Dir.

Elia KazanWrit.

Budd Schulberg, based on Mike Johnson's notesw/

Marlon Brando, Karl Malden, Lee J. Cobb, Rod Steiger, Eva Marie SaintThe nation-wide poster billed Waterfront as "The Story of the Redemption of Terry Malloy", but the story would turn out to be about much more than just one young man rising above a one dimensional role he'd gotten duped into by "family".

Kazan had been looking to make a film specifically about the waterfront monopolies of the day, and had been working with muckraker Arthur Miller on a lead on Red Hook in Brooklyn. They eventually deserted the project. With moral support from tough, real-life Hoboken character and waterfront veteran Tony Mike and a rough screenplay from Schulberg, Kazan gave the revised idea to Darren Zanuck. Although the pioneering producer had worked a waterfront job as a young man and probably had convictions supporting the film's best interests, he passed on it. It's presumable he was trying to avoid the same sort of political pressures that had caused Kazan and the tireless Miller to abandon their original and extensive body of research.

When independent producer - a title practically unhead of then or now - Sam Spiegel stepped up to produce he was, in Kazan's words, "a downer on uppers". He needed a film and fast. Paring down the script with Schulberg night after night resulted in a film that would take away seven major honors at the Academy Awards.

Having co-founded the Actor's Studio [1] in New York City in 1947 for the express purpose of teaching method acting, Kazan knew what sorts of actors he needed for this project. Brando's working-man-trying-to-make-good is a steadfast and reliable sort, a true testament to the wonders of "the Method". Rather than creating a dominating character that the rest of the cast would either have to try to outdo or react to at every turn, he allows for a great tenderness and vulnerability which chisels Terry Malloy in a way that swagger and unyielding masculinity never could.

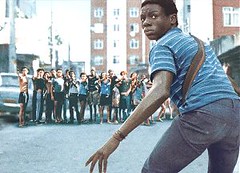

The film opens using him as bait so that the bad guys can push somebody off of a roof. This doesn't sit well with Malloy, who discovers his own part in the crime ex post facto. To augment this flaw, Schulberg presents us with the dead guy's younger sister - in the luminous form of Eva Marie Saint - as Malloy's love interest, managing in one stroke to connect all of our hero's struggles. The secret that distances him emotionally from his girlfriend creates problems in her life as she and her poor, old dad struggle to make ends meet in a family that has lost its breadwinner. His relationship with his older brother, a dyed-in-the-wool waterfront sycophant, begins to run threadbare as their loyalties divide. Rod Steiger plays this down effortlessly, as a boy following the path of his father, as if being a mob thug were the only role that someone like him could ever aspire to claim. When the more sensitive brother begins revolting against the tyrrany of union racketeer Johnny Friendly - a flawless Lee J. Cobb [2] - it becomes a raw scene of mano y mano in which Terry Malloy rips his dignity back from the hands of the man who would have every other man on the stagnant docks cowering under him. Our hero takes the working class with him, restoring dignity to his girl's family, and saving the day.

This is a triumphant story of more than just the redemption of one man against a mob of indifferent gangsters, it's a story that had blue collar working types from every industry lined up for blocks, their crusty uniforms and worn faces proclaiming the arrival of a film worth spending an hour's wages on. Every once in a while, it's good to know that a box-office smash is really worthwhile. It stands up to that benchmark to this day with cinematography, acting, and writing the quality of which gets harder and harder to find. It is, perhaps, Kazan's finest film. [3]

[1] Native to American cinema, this study of Stanislavski's ideas, directed by Lee Strasberg, was eventually also picked up in Los Angeles, with the opening of the Actor's Studio West in 1966. However, many of the notable actors from the '50s and '60s were the rangey New York types, whose ilk included Montgomery Clift, James Dean, Julie Harris, and Paul Newman, as well as Al Pacino, who became co-artistic director (with Ellen Burstyn) upon Strasberg's 1982 demise.

[2] If you're riveted by Cobb's performance in this, check out the Brothers Karamazov, which earned him a second Academy nomination four years later for the foul, despicable Fyodor. Or even 12 Angry Men, which is just brilliant single-setting writing and acting.

[3] Considering that this is the man who brought us A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Gentleman's Agreement, A Streetcar Named Desire, Viva Zapata! and East of Eden, that's saying something. Of course, it's hard to go wrong when you have the Actor's Studio, not to mention the complete works of Tennessee Williams, as your major - and abundant - resource.

Labels: Film, Kazan, Reviews