Swing Time (1936)

Dir. George Stevens

Writ. Erwin S. Gelsey, Howard Lindsay, and Allan Scott

w/ Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Victor Moore, and Helen Broderick

"I just pick myself up, dust myself off, and start all over again..."

With song lyrics that have wound their way into the national psyche over the decades, Swing Time possesses an unforgettable slice of Americana. The magic created by their sweet naiveté perhaps the most lasting quality of the pairing of Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire, the real pyrotechnics show best when they dance. Although he would go on to partner with Lucille Bremer, Rita Hayworth, Eleanor Powell, and Cyd Charisse, none would ever please the eye so much as Ginger. She moved in and out of his arms without hesitation, light as breath and lovely as wine.

One of the most novel pastimes of apple pie American theatre seems to be the sporting, good old boy sense of fair play in foul. Conned out of money and a wedding by his dance troup, Lucky hops a train with nothing but the tuxedo on his back, a lucky quarter, and aging sleight-of-hand magician, Pop. When he asks a girl on the street for change, he almost loses the lucky coin. He follows her to the dance hall where she gives lessons, and before you can say "jitterbug" they're dancing as though they were meant for each other.

So is it all that surprising when the charming Lucky, a gambler who doesn't like to give up on a good thing, finds himself in a fix when he falls for the graceful Penny? Not really, but in a film created around a dancing couple, the love story will evolve no more straightforwardly than the dance steps. He still has a fiancee back home, waiting for him to cough up $25,000 so that they can marry; but, of course, she can't dance. In a great scene where he's hoping that they don't have to fall in love, that they can just ignore the problem and it will go away, just the opposite happens. Never underestimate the power of nagging your lover over some missing kisses by singing in the midst of winter's white delight.

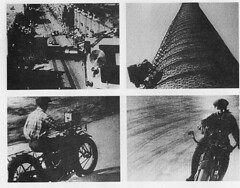

Some notable numbers surface, including a somewhat disturbing blackface "Beau Jangles" dance sequence. Its inclusion in theory rather than in practice sends a haunting echo of both political and showbusiness history, but watching Fred dance a much more agressive jig with those chilling silhouettes makes for great cinematography, the kind that can send tingles down one's spine at nearly any age. A stark reminder that his was a different world, it's important to peel away the layers, because what we're getting when he performs for a fictional audience is a look at a look, removed from the easier to watch foreground. Whether or not audiences in 1936 felt the same pulse remains questionable.

In strict terms of film value, the "Beau Jangles" number acts as an exciting bridge, filled with all of Lucky's darkest thoughts that couldn't have been spoken aloud and are better expressed through dance. The rest of the time, judging from the way he and Ginger cut a rug, we have a pretty good idea what's on his mind.