Communicative Activism in Eugene V. Debs' Statement to the Court

A while ago, Debs was brought to my attention, and I fell in love with his speech. As it turns out, I have more socialism in me than even I would have previously suspected. When I was given the option of doing a term paper in my rhetorical theory class -- an option I could forego at meager expense to my grade in the class -- I jumped at the chance to critique Mark Twain. I had just bought a nice volume of his essays.

And then I remembered Eugene V. Debs, to whom I was introduced in this fine essay by local media artist Lucas McNelly. What follows is a first dig at ideological criticism. Please be kind.

"Your Honor, years ago I recognized my kinship with all living things and I made up my mind that I was not one bit better than the meanest of the earth...I said then, I say now, that while there is a lower class, I am in it; while there is a criminal element, I am of it; while there is a soul in prison, I am not free...

"I am thinking this morning of the men in the mills and the factories; of the men in the mines and on the railroads. I am thinking of the women who for a paltry wage are compelled to work out their barren lives; of the little children who in this system are robbed of their childhood and in their tender years are seized in the remorseless grasp of Mammon and forced into the industrial dungeons, there to feed the monster machines while they themselves are being starved and stunted, body and soul. I see them dwarfed and diseased and their little lives broken and blasted because in this high noon of Christian civilization money is still so much more than the flesh and blood of childhood. In very truth gold is god today and rules with pitiless sway in the affairs of men.

"In this country – the most favored beneath the bending skies – we have vast areas of the richest and most fertile soil, material resources in inexhaustible abundance, the most marvelous productive machinery on earth, and millions of eager workers ready to apply their labor to that machinery to produce in abundance for every man, woman, and child -- and if there are still vast numbers of our people who are the victims of poverty and whose lives are an unceasing struggle all the way from youth to old age, until at last death comes to their rescue and lulls these hapless victims to dreamless sleep, it is not the fault of the Almighty: it cannot be charged to nature, but it is due entirely to the outgrown social system in which we live that ought to be abolished not only in the interest of the toiling masses but in the higher interest of all humanity..."

-- excerpt of Debs’ Statement to the Court for Violating the Sedition Act [1]

His earliest thoughts shaped by the French and German romanticists of the Enlightenment, due to his father's guidance, the chronology of Debs' life could be encapsulated (by someone more ambitious) as a study in dialectical reasoning. In 1869, the fourteen-year-old Indianan began working in a railroad shop. Within six years, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen elected him secretary and he became editor of the group's magazine, devoting himself to the union's success. After being laid off, he found work as a city clerk, ascended to the Indiana legislature and eventually founded the American Railway Union, bypassing the inflexible unions already in existence. As the Union's President, he headed a strike against the Great Northern Railroad in 1894 and won. The Union disintegrated in 1895 when he was arrested and jailed for failing to obey a federal injunction to cease the Chicago Pullman Palace Car Company strike. He began reading Marx while confronted with the prison conditions and soon concluded that labor and social issues were one and the same.

1898 found Debs organizing the Socialist party of America, running for the U.S. Presidency in 1900 on the party's ticket and winning a weak but encouraging 96,000 votes. He would run again four more times, garnering 800,000 votes for his third campaign in 1912. But it was during his second prison sentence in 1920, while serving ten years for his outspoken criticism of Wilson's handling of both foreign and domestic affairs – specifically, the U.S.'s participation in WWI and the imprisonment of many conscientious objectors to the war for sedition – that Debs gained 915,00 ballots, or 6% of the popular vote. His crime was communication, clearly forbidden by the 1917 Espionage Act that accompanied America dipping its oar into the brewing European firepot. During the trial, Debs gave a speech that compelled world figures – Lenin and Shaw – to argue for his release, but he remained behind bars until 1921 when demonstrators crying for amnesty for "prisoners of conscience" gave Warren G. Harding little choice but to meet their overwhelming demand. [2]

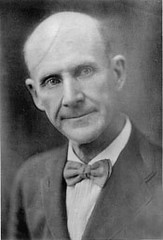

Often described as "magnetic," Debs' character and ethos was a tangible and apparent fact. "Straight from the Indiana heartland of America, lanky and bald, his forehead weighted with worry and his cheeks crinkled with laughter, Debs was the symbol of integrity," John Patrick Diggins wrote of him. "His life history reads almost like a socialist morality tale." The forces surrounding and shaping him in a time of great violence reflect most readily in his study of Marx. Although the union leader would claim later and often that the bloody events of the Pullman strike precipitated his conversion to socialism, democratic reformism remained his political leaning until 1896. His very description of the conversion betrays him. "At this juncture there were delivered," Debs said of the strike, "from wholly unexpected quarters, a quick succession of blows that blinded me for an instant and then my eyes opened – and in the gleam of every bayonet and the flash of every rifle the class struggle revealed itself." Not until having discovered Marx while in prison in 1895, though, would he have been able to draw that connection.

Debs' literary background informed his eloquence, but his time as a common worker gave him greater breadth and credibility with which to wield it. "Debs had the martyr's charisma, but he also possessed tremendous oratorical power." Those who heard him address a crowd recall the way he spoke well. "His tongue...would dwell upon a the or an and with a kind of earnest affection for the humble that threw the whole rhythm of his sentence out of conventional mold, and made each one seem a special creation of the moment." [3]

At New York's Grand Central palace on December 10, 1905, Debs delivered his Industrial Unionism speech to great applause even as he discussed dehumanization: "When the capitalist needs you as a working man to operate his machine, he does not advertise, he does not call for men, but for ‘hands’; and when you see a placard posted ‘Fifty hands wanted,’ you stop on the instant; you know that that means YOU, and you take a bee-line for the bureau of employment to offer yourself in evidence of the fact that you are a ‘hand.’ When the capitalist advertises for hands, that is what he wants. He would be insulted if you were to call him a ‘hand.’ He has his capitalist politician tell you, when your vote is wanted, that you ought to be very proud of your hands because they are horny; and if that is true, he ought to be ashamed of his." [4]

Comparing the tone of his Grand Central palace address with that of the opening statement of his sedition trial leaves little doubt as to Debs' audience consideration within his discursive practices. Oscar Wilde biographer Frank Harris noted the quality in his tribute to Debs in Pearson Magazine in 1919, after having sampled some of his writing on literary giants that Harris later published as the book Master Spirits. "His writings reveal the man: he deals in nothing but praise and yet his praise say of Ingersoll is subtly differentiated from his praise of Wendell Phillips and his admiration of the Hoosier Poet has different roots from his admiration of Eugene Field."

Harris' respect afforded Debs some literary respite from the political persecution he suffered at that time, while also augmenting anti-administration sentiments that arose from or were exacerbated by his imprisonment. "As Bernard Shaw wrote to me the other day his sentence is a disgrace to America and a disgrace to republican institutions," Harris declared. "We are all ashamed by his punishment, disgraced, all of us, save the justices and President Woodrow Wilson who is chiefly and forever responsible for punishing one of the noblest of men." [5]

Considered to be one of the most influential socio-political voices of the twentieth century, Debs' oratorical power has spread far and wide, impacting literature, government policy and the evolution of labor practices. In 1976, after the union leader's death, President Carter reinstated the U.S. citizenship that had been abrogated for the exercise of First Amendment rights. His speech made to the court during his trial for sedition remains his best-known and deserves some scrutiny.

Because Debs invoked mythical and spiritual figures and not strictly socialist themes with his 1918 sedition trial speech, it will prove more rewarding to use two main lenses, one examined by Jürgen Habermas and the other fashioned by him. When the second generation Frankfurt scholar considered Ernst Cassirer's contribution to humanism with The Liberating Power of Symbols, he noted that the German professor's particular "philosophy of symbolic forms" – the means by which humans relate to each other symbolically – rests upon "the four worlds of myth, language, art and science." Habermas believed that this philosophy divested humankind of its subjugation to the discursive practices of those he would deem irrational and less-than-enlightened. "The humanistic legacy which Cassirer bequeaths to us through his philosophy," he wrote, "consists not least in sensitizing us to the fake primordiality of political myths. Cassirer makes us wary of the intellectual celebration of archaic origins, which is widespread today, as in the 1930s."

Habermas' words concerning Cassirer have as much relevance to Debs' situation before the 1930s as they do to the decade. The significance of a mass culture reveling in archaisms manifests itself in an evidential pertinence to the evolution of communication as a social theory, especially as the advent of the Great Depression and the continued heightened prevalence of capitalism over socialism held repercussions for subsequent symbolic interaction and its control in such forms as the rooting out of suspected socialists through blacklisting, McCarthyism and the increasingly ubiquitous operations of the inextricably linked political and economic spheres.

In the context of Debs' speech, it will be essential to give deference to Cassirer's thoughts on the worlds of myth and language – specifically, on his attention to historical allegories. "Cassirer derives philosophical thoughts from allegories – changes in the philosophical concept of freedom, for example, from the transformations of the symbol of Fortuna: 'Fortuna with the wheel which seizes hold of man and spins him around, sometimes raising him high, sometimes plunging him into the depths, becomes Fortuna with the sail – and it is no longer she alone who steers the ship, but rather man himself who (now) sits at the rudder.'" [6]

Habermas’ own ideological contribution can be overviewed in the study of his Theory of Communicative Action by Yugoslavian philosopher Ljubisa Mitrovic, who separated the German philosopher's neo-Marxist tendencies within critical theory from his movement towards a new post-Marxist social theory. "Despite Marx's paradigm of production and social labor as the basic category around which the social Marxist theory was constituted, Habermas founded the paradigm of communicative action, that is, of communication. In his work there is a distinct requirement for convergence and synthesis of the action theory with the system theory; thus, the traditional type of rationality is offered an alternative as communication mind, intersubjective reality." [7]

En route to building his theory of communicative action, Habermas contributed Communication and the Evolution of Society, which provides some useful theoretical genesis. Dubbing culture a "superstructural phenomenon," it calls for a reconstruction of Marxist theory attendant upon renewed historical materialism and examines "linguistically established intersubjectivity."

"The structures of linguistically established intersubjectivity – which can be examined prototypically in connection with elementary speech actions – are conditions of both social and personality systems. Social systems can be viewed as networks of communicative actions; personality systems can be regarded under the ability to speak and act. If one examines social institutions and the action competences of socialized individuals for general characteristics, one encounters the same structures of consciousness. This can be shown in connection with those arrangements and orientations that specialize in maintaining endangered intersubjectivity of understanding in cases of action conflicts – law and morality. When the background consensus of habitual daily routine breaks down, consensual regulation of action conflicts (accomplished under the renunciation of force) provides for the continuation of communicative action with other means. To this extent, law and morality mark the core domain of interaction."

Also of critical import is his discussion of the connection between ego and group identity: "There are also homologies between the structures of ego identity and of group identity. The epistemic ego (as the ego in general) is characterized by those general structures of cognitive, linguistic, and active ability that every individual ego has in common with all other egos; the practical ego, however, forms and maintains itself as individual in performing its actions. It secures the identity of the person within the epistemic structures of the ego in general. It maintains the continuity of life history and the symbolic boundaries of the personality system through repeatedly actualized self-identifications; and it does so in such a way that it can locate itself clearly - that is unmistakably and recognizedly - in the intersubjective relations of its social life world. Indeed the identity of the person is in a certain way the result of identifying achievements of the person himself." [8]

Mitrovic took care to delineate further between Marx and Habermas. Both theorists "believe in good human nature," and both eschew capitalistic means of organization; but Marx grounded his principles in the solidarity of communism, while Habermas roots his theoretical explications in communication processes. Their difference is slight but fundamental. "The normative basis of Marx's theory is formed of the value theory and the theory of exploitation and alienation, discarded by Habermas, while he, at the same time, speaks about alienation in terms of privileges and deprivation. The normative basis of Habermas' theory is related to speech and communicative action."

Marx's influence upon Debs is as undeniable as Debs' impact upon social theory. Thus, it will be necessary to reflect upon both theorists in order to critique Debs in a proper light.

In the opening five paragraphs of his statement, Debs uses the first person singular and sonorous repetitions to advance his belief that "all men are created equal," while simultaneously asserting his maturity, which he then wraps in a tone of humility. He declares the Espionage Law a "despotic enactment of flagrant conflict with democratic principles" and restates his belief in the necessity for change, adding that peaceable change is preferable and leaving the sentence unfinished on purpose. His comparison of the workplace to prison as he recalls his boyhood reminds the court of his conscious choice to remain a working class member and advocate, despite his proven ability to have ascended to political power in Congress. In the fifth paragraph, he introduces the working class – men, women and children – and blasts Christianity for both inviting and condoning modern industrial labor conditions.

In the sixth paragraph, Debs strategically changes the point of view. He sets himself up as representative not of himself but of the working class that he has introduced. As their advocate and using the same humility in which he swathed his earlier words, he addresses the governing officials. He speaks of the material wealth that "we" have, if only the full potential and rights of the "they" – the working class – can be recognized.

Habermas discusses ego identity in terms not mutually exclusive with group identity. "No one can construct an identity independently of the identifications that others make of him. These are, naturally, identifications that others make not in the propositional attitude of observers, but in the performative attitude of participants in interaction." With this in mind, Debs' opening declaration that "while there is a lower class, I am in it; while there is a criminal element, I am of it; while there is a soul in prison, I am not free" clarifies his understanding of his own identity, especially in light of his later words, "I could have been in Congress long ago. I have preferred to go to prison..." By identifying himself as a man of the people, he sets the stage for promoting the ideology of socialism through a series of deceptively simple introductions.

By the sixth paragraph, in which Debs glories in the abundant material and resources America possesses, he switches from the first person singular to the first person plural. Habermas defines these pronouns' relational values in terms of audience. "The expression 'we' is used not only in collective speech actions vis-à-vis an addressee who assumes the communicative role of you, under the reciprocity condition that we in turn are you for them. In individual speech actions, we can also be used in such a way that a corresponding sentence presupposes not only the complementary relation to another group but that to other individuals of one's own group." This "asymmetry" enables two audiences that can be mutually exclusive – but don’t have to be – to be addressed at once.

In this example, Debs accomplishes that task: "In this country – the most favored beneath the bending skies – we have vast areas of the richest and most fertile soil, material resources in inexhaustible abundance, the most marvelous productive machinery on earth, and millions of eager workers ready to apply their labor to produce in abundance for every man, woman and child..." By using the first person plural, Debs extends the invitation to his captors to become involved in a labor force that they are not necessarily already a part of, and makes it the responsibility of individual members of his audience to decide to which group he or she wishes to identify.

Because of its open-ended quality, such an invitation acts rather slickly. It does not single anybody out as oppressor, but merely raises the question of responsibility and choice. It might be difficult to notice the effects of the point of view switch at all in so smooth a transition, except that Debs also refers to those for whom he has appointed himself to speak: "they" – the working class whose voice has been denied. Habermas spoke of language and choices in 1965 when he said, “The human interest in autonomy and responsibility is not mere fancy, for it can be apprehended a priori. What raises us out of nature is the only thing whose nature we can know: language. Through its structure, autonomy and responsibility are posited for us.” Thus Habermas renders language the source of individual responsibility. In this sense, Debs can be seen as not only exercising his responsibility but also providing a framework for others to do the same. That his speech is an exercise of his rights for having previously, similarly exercised those same rights should not be dismissed; if the only thing we can know is language, and that ability is crippled, then the state imposing such regulation falls outside of the knowable. [9]

Debs hinges the rest of his statement not upon his advocacy of the working class or on Socialism itself or even (directly) on the hypocrisy of the State. These words are meant to inspire, encourage and bolster the Socialist movement. His pivotal joint, the focus he uses to separate his representation from the framework of his speech, is an allegorical introduction: “Mammon” and “the Almighty.” The epic, timeless struggle between good and evil serves as an analogous metaphor for the ongoing class struggle that has brought Debs to trial; but, more importantly, it acts as a red herring to pull attention away from his true motive: to prove that all men are created equal and free, and that any government not reflective of this truth shall justly, rightly perish.

The original word Mammon is the Aramaic rendering of "riches," but its Greek counterpart, mamonas, was personified in the parable of the Unjust Steward, in Luke 16:9-13. Its appearance in the gospels laid it open to various scholarly usages, interpretations and translations into other languages. Augustine entitled the Sermon on the Mount "Lucrum Punice Mammon dicitur" and Gregory of Nyssa claimed Mammon to be a pseudonym for Beelzebub. Throughout the Middle Ages, the word would continue to symbolize the connection between avarice and demonization. Later, it would collect a wealth of metaphorical garments, such as the guardian of a "cave of world wealth" in Spenser's Faerie Queen, or the fallen angel with similar duties in Milton's Paradise Lost. "For Thomas Carlyle in Past and Present, the 'Gospel of Mammonism' became simply a metaphoric personification for the materialistic spirit of the nineteenth century." [10]

Cassirer sheds light on the processes by which the acceptance and incorporation of Mammon even into the modern age occurred. "As soon as the spark has leapt across, as soon as the tension and the affect of the moment have been discharged in a word or mythical image, then a reversal can start to occur within the mind...Now a process of objectification can begin which advances ever further. As the activity of human beings extends over an ever wider area, so a progressive subdivision and ever more precise articulation of both the mythical and linguistic world is achieved."

Were Debs' usage of Mammon implicitly secular, a simple line could be drawn to Carlyle's more vernacular treatment of the word; however, Debs' schooling in classical texts and his invocation of "the Almighty" goes beyond the association of capitalistic tendencies with man's nature, a factor he brings to denouement as readily as God's part in man's state: "...it is not the fault of the Almighty: it cannot be charged to nature, but it is due entirely to the outgrown social system in which we live." His argument ties the capitalistic forces that have sentenced him to money as the "root of all evil," and not as a merely harmless, secular pursuit. His distinction between modern Christianity – or, more accurately, what passes for it -- and the gap between evil and good is as clear as his connection between money and godlessness, which he equates with "the high noon of Christian civilization."

Debs' avoidance of calling upon God as a Savior or of denouncing man for his inaction strengthens his words as both an appeal to man's better nature and as an epic metaphor for which, Habermas asserted, there is no response. “Mythology permits narrative explanations with the help of exemplary stories; cosmological world views, philosophies, and higher religions already permit deductive explanations from first principles (the originary actions of myth having been transformed into "beginnings" of argumentation, beyond which one cannot go)..." In this way, Debs calls for responsible living and action, both by way of rhetorical prowess and by example. By so doing, he reaches beyond the first three forms of action that Habermas outlined -teleological, norm-regulated and dramaturgical - into the fourth form: communicative action.

As in Cassirer's allegorical presentation of Fortuna, which depicts the surrender of captainship to man in such a way that man's responsibility to free himself from bondage is self-evident, Debs reaffirms his belief in man's similarly conscious role by taking the power of Fate away from not only Mammon but from the Almighty as well. In this sense, the denuding of mythological forces strips man of his dependence upon Divine intervention, his ability to blame his misfortune upon others, and attempts a fulcrum point for catalyzing "the great struggle between the powers of greed and exploitation on the one hand, and on the other, the rising hosts of industrial freedom and social justice," as Debs characterizes the class struggle towards the end of his speech.

This reference to an epic class struggle should not go unnoted. Habermas took exception with the evolution of myth into the political realm. "Only with the transition to societies organized around a state do mythological world views also take on the legitimation of structures of domination (which already presuppose the conventional stage of moralized law)." He argued that the usages of myths were legion, serving as a solid basis upon which rationalization could be achieved through dogmatization. "The further transition from archaic to developed civilizations is marked by a break with mythological thought. There arise cosmological world views, philosophies, and the higher religions, which replace the narrative explanations of mythological accounts with argumentative foundations. The traditions going back to the great founders are an explicitly teachable knowledge that can be dogmatized, that is, professionally rationalized."

It is here that Debs' communicative endeavor and Habermas' more secular ideal speech situation part ideological ways somewhat. Debs returned to the romantic notion of "the Almighty" as a benevolent promise to man that his actions are not in vain when he alluded to Psalm 30:5 in the last paragraph of his speech: "For his anger endureth but a moment; in his favor is life: weeping may endure for a night, but joy cometh in the morning." Man's responsibility to action and the betterment of the world through the workforce is clearly as earth-bound, by definition, as the Habermasian struggle towards rationality, but his reward may yet lie beyond the horizon of the rational world.

1. Debs, Eugene V. “1918 Statement to the Court Upon Being Convicted of Violating the Sedition Act.” AmericanRhetoric.com. Transcribed by John Metz and David Walters, E.V. Debs Internet Archive. Online. Accessed: 4 Oct. 2006. Available: http://www.marxists.org/archive/debs/works/1918/court.htm

2. Young, Marguerite. Harp Song for a Radical. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999.

3. Diggins, John Patrick. The Rise and Fall of the American Left. New York: W. W. Norton, 1992.

4. Debs, Eugene V. Debs Speaks. Ed. Jean Y. Tussey. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1970.

5. Debs, Eugene V. “Pastels of Men.” Pearson’s Magazine, Inc. 1919: full article.

6. Habermas, Jürgen. The Liberating Power of Symbols. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 2001. Translated: Peter Dews.

7. Habermas, Jürgen. Communication and the Evolution of Society. Boston: Beacon Press, 1979. Translated: Thomas McCarthy.

8. Ljubisa, Mitrovic. “New Social Paradigm: Habermas’s Theory of Communicative Action.” Facta Universitatis. Vol.2, No 6/2, 1999, 217-223.

9. Burleson, Brant R. and Susan L. Kline. “Habermas’ Theory of Communication: A Critical Explication.” The Quarterly Journal of Speech. 65, 1979, 412- 28.

10. “Mammon.” Wikipedia. Online. Available: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mammon . Accessed: 29 Oct 2006.