Unspoken Cinema: Music & Experience as narrative force...

Yesterday evening, as part of my promise to myself to extend my visual foray into foreign lands, I ventured over to Melwood Avenue, that tiny dead-end street that only those familiar with Pittsburgh know to rest within city limits. Come to think of it, rest is a funny word, really. It sort of hunkers in the nether regions of the city, as disconnected from its "suburb" of Oakland as it is from the greater Three Rivers area. You know that alley that doesn't go anywhere in that B horror film with the zombies and the sunglasses and the shopping? Existentially speaking, that's where Filmmakers crouches on the psychic map -- disintegrating curbs, fire hydrants and all.

I parked my car as I used to do routinely only a few years ago and prepared myself for an evening of short videos collected by a hodge-podge of local filmmaking hopefuls who had gathered in the even seamier suburb of Braddock under the banner Film Frenzy. The spearheaders of the grassroots co-op wish to see the thing take off in a not-yet-envisioned way that lends itself to collaboration in a way not-yet-defined; and, you can read more about the specifics of their overall vagueness in Bill O'Driscoll's write-up on it in last week's City Paper. Although somewhat more like an exercise, the idea held enough interest -- at least in terms of what young people are doing with and thinking about video these days -- that I'd decided I could spare the scant dollars and even looked forward to the event despite my disconnection with a school I had once had great hopes for, but with which I so quickly became disenchanted.

[Yes, intrepid, self-sacrificing supporter of the arts...that's me. Plus, I had a ton of work which I decided I wouldn't get to after pacing between my kitchen and living room for half an hour.]

Although I was certain I was right on time, projection had already begun when I found the room. I walked to the nearest easy-on-the-neck seat, well in front of the majority of the sparse audience, and contritely breathed silently and stayed still. Within seconds, the fellow sitting a half a row down in the same row began clicking his pen. The room was quite dark and I could not actually see him, but the way he clicked the pen decidedly made him a man. Don't ask me how I knew this...I just did. The remainder of the evening's proceedings will be an alternating dialogue of my impressions of the film in plain type and my italicized impressions surrounding the man who -- to aid you visually as you read -- looked a hell of a lot like Sideshow Bob, but in dockers and tweed, and sporting more neurotic ticks than just pen-clicking.

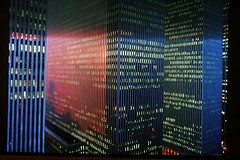

The screen to which I am first introduced is filled with somber but hopeful cityscapes in which buildings shape unique corridors and reflect time-lapsed skies. It reminds me a great deal of the architecture photographs used to advertise Filmmakers at local theatres like the Waterworks in the good old days, before advertising became the mainstay of pre-movie watching and waiting. As someone who considers movie theatres to be her only church, I have often thought of that ten to twenty minutes before a show as meditation time in which to sip coffee and reflect on all the events of a week which conspired together to bring me to that particular moment. Such meditations have a naturally soothing and invigorating effect that put me in the right frame of mind to not only watch the film but to tune out nearly everyone around me. Pleasant stuff.

Seeing something that reminded me of cinematic life before "the Reel thing" put a smile on my face. The smile lingered; the reverie vanished almost instantly. A fairly steady stream of collaged images began to take on uniformity and compression. Rows of brownstone filmed from the back revealed unending lines of windows, fire escapes and framework, all alike, all static.

Click, click. Why is he looking at me? This is fascinating.

Click.

The camera traveled over unidentifiable rubble -- decomposed building materials, presumably -- to expose the parts of urban life most cameras avoid in the U.S. The pictures look like shots from third-world countries, and the sight of the indistinguishable architecture of unidentifiable metropolitan area after metropolitan area turns oppressive.

Dresden. This looks like what the government tried to do in Dresden after the war. It's not a suburb, and these aren't developments, but this is the imposition of uniformity upon a society.

Click.

My society. Not that it matters, but where the hell is this? Click, click.

Buildings start imploding, and it occurs to me for the first time that the "Film Frenzy" folks have really outdone themselves. I begin to wonder, as the implosions become more elaborate -- high rises set in difficult nooks between vulnerable buildings, and even a bridge -- if what I'm actually seeing is stock footage. If it is, I want to know where they got it from because it's not just that this isn't Braddock. It's beautiful -- and not just the capturing of these moments because, by themselves, I wouldn't think much of the shots. The compositions lack judgment, creating a somewhat pretentious neutrality; the juxtaposition of the framing with the score, though, strikes whole sets of emotions in the viewer. Instructive musical composition, if you will, sears these images of destruction with an acute sense of medieval-like exuberance. The oppression, like the Dark Ages, can not go on forever, it sings. These buildings must fall, were meant to fall.

Within moments, people on the sidewalk are incorporated into the collage matrix.

They're all wearing heavy, starched polyester.

Any suspension of disbelief that this could have been shot in the digital age corrects itself, and I look more closely at the blurriness and decide the film was probably shot on 16 mm. It's still quite blurry in places on purpose, but occasionally even the diminished screen gives itself away.

Click, click. Legal pad page turning. Hmmm...I'm guessing that this isn't a Film Frenzy production after all. This must be the opening act. Hell of an opening act. Click. I wonder if he's upset because I got here late or because I haven't paid yet. Hmm...

The filmmaker -- who I find out later is Geoffrey Reggio -- recreates the concept of mass movement over and over again with Ron Fricke's incredible cinematography. Some of the shots are just generally blurry and planeless. People pass by in slow motion impressions of themselves. They fast forward up escalators and through fast food meals in waiting stations, giving away their nervousness and inability to stay still even when talking to each other, eating or simply watching the masses of people around them. The camera plays with both fast and slow motion in such a way that the lives of the people, the character of the people and any other identifiers that mark them as humans who interact in any way besides movement gets stripped away. These aren't people at all, throughout most of the film. They are predictable, unstoppable vectors that have no destinations, no motivations, only kinetic reality.

Fricke soon switches to fixed focal plane shots on the sidewalks, and faces come into sharp relief for a moment before stepping back into anonymity. As the film moves into an area that I realize was once considered to be visually stunning, I recall a lot of the photography work I used to study, as gathered by John Hedgecoe in The Photographer's Handbook. Instead of opening the shutter to allow car lights to blur, though, the film camera uses time-lapse and more sped-up footage to show the traffic patterns at night, the infrastructure coilings. All the while, the music cues and instructs the facial muscles and other various pressure points. I should have realized why at the time, but it has been too long since I listened to Philip Glass, and I must admit that I don't speak a word of the Native American Hopi language.

In case you haven't guessed it by now, the film I am watching turns out to be Koyaanisqatsi (1982), nine years in the making and the first of what Reggio is still finishing: a trilogy of collage films. His subsequent film, Powaqqatsi (1988), was much less well-received, and he is currently working on Naqoyqatsi. To curtail my brief effort to encourage viewership of at least the first film, I'll mention what Reggio's short bio (linked above) does not: he was disrobed in 1968 by the Roman Catholic Church for what Ephraim Katz cites as "ideological insubordination" in The Film Encyclopedia. As should be expected from someone so outcast from the mainstream, each of his films hinges upon a central theme: life out of balance, life in transformation and life as war, in respective chronological order.

Many frames in the film held powerful symbolism.

Many frames in the film held powerful symbolism.

Some moments were so hard to handle that at one point in the film, I only stayed for the credits. It's not my style to walk out of a movie that I know to be well made, even when I find its study of dehumanization to be overwhelming. I just don't like pain that much. But I was glad that I stayed. At the end, after the oppressive images finally ended, after the last person on the street who obviously didn't want to be filmed and leered at the camera with suspicion and hostility, the camera focused on an ancient Native American sketch and informed the viewer of the word which had been sung repeatedly in Gregorian-style chants a la Glass' cruel conductor's wand:

Koyaanisqatsi, a Hopi word meaning 1. crazy life, 2. life in turmoil, 3. life disintegrating, 4. life out of balance, 5. a state of life that calls for another way of living.

Koyaanisqatsi, a Hopi word meaning 1. crazy life, 2. life in turmoil, 3. life disintegrating, 4. life out of balance, 5. a state of life that calls for another way of living.

The lights come up to reveal this jittery filmmaking instructor and a scant class that I did not turn around to viddy. He looked at me but once or twice as he talked about how he hoped that everyone had gotten something out of the film, and that it should give them a fairly solid idea of what film -- although undeniably containing a point -- without narrative does, letting the story happen in the viewer's mind to a great extent, etc. He points to the dehumanization of mass culture and to the textual shots of the people on the street, noting that these cuts have interfered somehow with these people's lives, and that we see the frays.

He's obviously very disappointed that his class isn't engaging him in conversation about it, and he's nervous about that, too, and my heart goes out to him. And then his cell phone goes off. He's got one of those nature sounds instead of a digital tonal, and one of the class members snickers. It recalls all the reasons I don't miss being a student at Filmmakers. I prefer wide open spaces and quiet repose and, failing that, I'll take my modest apartment and a cup of tea.

...All of which is a polite euphemism for I'm too old for these reindeer games.

When it becomes excruciatingly clear that his students have nothing to say, I stand up and apologize for crashing his class and tell (lie to) him that I had gotten bad directions. This was the mini screening room. I had wanted the other one. I also tell him that this was probably a much better viewing than I could have hoped for that night, and thanked him. He seemed relieved, and told me that he was glad I had gotten something out of it.

Indeed I did, Sideshow Bob. Indeed I did.

Two major factors arise as I consider the open-ended qualities of a non-narrative film like Koyaanisqatsi. The first is the addition of musical score. Whether the score acts as a driving force to the film's visual composition or as a counterpoint to the visual workings, the score instructs the viewer in ways less open-ended than the visual text. Tensions resulting from internal and external rhythms, reliefs provided by harmonies and dynamics of tone and pitch all provide rich and complex texts of their own. While this may seem like a passé reiteration for a study of "contemplative cinema," the fact remains that films like Koyaanisqatsi have been and still are considered to be non-narrative film despite their heavy reliance upon an inherently narrative-producing medium engulfing an entire realm of scholarship and technique all its own.

The second major factor I see as inherent in the non-narrative experience remains the consistent human expectation of story-telling in art forms. Because it is a natural and fundamental human process to relate through narrative, when we are approached by and engaged with an art form that purports to (or that scholars identify as) being non-judgmental and solely experiential that an audience will inevitably -- as a collective or individually -- try to arrange the film as a narrative to make sense of it. In and of itself, this process feels right, but it also trends toward a deeper aspect of human narrative expectations; i.e., because the director has selected material and arranged it in a certain way, the audience will not be satisfied with a narrative structure that is arrived at solely through experience, but seek to determine the author's intent, the author's point of view and what the author is trying to say.

The very act of experiential non-narrative viewing, in this sense, has the ability to negate the wishes and efforts of the director to create a freely interpreted form as the audience seeks to find the narrative through the film's various elements -- both what's used, and what is not.

The second major factor I see as inherent in the non-narrative experience remains the consistent human expectation of story-telling in art forms. Because it is a natural and fundamental human process to relate through narrative, when we are approached by and engaged with an art form that purports to (or that scholars identify as) being non-judgmental and solely experiential that an audience will inevitably -- as a collective or individually -- try to arrange the film as a narrative to make sense of it. In and of itself, this process feels right, but it also trends toward a deeper aspect of human narrative expectations; i.e., because the director has selected material and arranged it in a certain way, the audience will not be satisfied with a narrative structure that is arrived at solely through experience, but seek to determine the author's intent, the author's point of view and what the author is trying to say.

The very act of experiential non-narrative viewing, in this sense, has the ability to negate the wishes and efforts of the director to create a freely interpreted form as the audience seeks to find the narrative through the film's various elements -- both what's used, and what is not.

Labels: Audience, Film, Music, Non-Narrative

11 Comments:

Great experiential analysis Johanna! I liked it, even though I didn't have the chance to watch Koyaanisqatsi yet, but I don't know what to say about it. This film sounds fascinating, I wish I could see it. Is it more of an abstract documentary or an Avant-Garde montage? I can't really picture what it's like...

Your viewing and post-viewing analyses are very interesting, especially considering the audience behavior subjected to intense and "meaningless"(?) contemplation.

You make a good point about score. Music is by definition a narrative medium (unless it is contemporean music experiment), so it does add a sense of continuity to the film, even if the images lack it. That's why to me score is a step backward, as far as contemplative cinema is concerned. But I'm sure there are examples whith clever use of a musical soundtrack, like you say, either as an ironic counterpoint, or to favor meditation. Badalamenti's score (for Lync films) for instance is quite contemplative.

What you say about this human urge to make meaning of what we see, is also one thing CC stands up against. We have to let go, and learn how to take a visual experience without tracking a plot or a story.

Thanks for your great contribution, and sorry for not commenting earlier.

Thank you, Harry, and no apologies necessary -- it is enough that you read and liked it. I only wish I had a translation for you; but, unfortunately, my French is poor.

To call it either abstract documentary or avant-garde would not quite do it, although it contains elements of both. His use (invocation, really) of the Native American ideology sort of tends itself to a transcendental style that tries very hard to steer clear of labels.

That's a very astute observation about Badalamenti. Something I noticed once was that the theme song to Twin Peaks had the power to frighten and entrance more on its own than while listened to in conjunction with the film itself. And the Mulholland Drive score was probably the first time I noticed that Badalamenti perfectly accompanied Lynch's visual style without detracting from it one bit. It is true that without the music, the film would suffer; but when it rises, it seems like no other music could have possibly matched those frames.

I agree with your characterization of the CC in terms of letting the traditional sense of narration go by the wayside. One of the great obstacles to this is codification -- of semiotics -- which I think hinders the process of film watching more than it enhances. If a film with traditional narrative is a prison cell, then semiotics is the manacle. While I do not discredit the entire world of film scholasticism in one fell swoop, I think it is important to recall that the difference between film and reality remains our guiding parallel between the liberation of ourselves through culture and its application and liberation itself.

If we are to lose sight of that, then why ever bother to watch a film again?

This is one of my favorite films ever though, paradoxically, I almost never watch it because it's too painful.

Whether the score acts as a driving force to the film's visual composition or as a counterpoint to the visual workings, the score instructs the viewer in ways less open-ended than the visual text.

Both, actually: Reggio edited the film, then Glass composed the music, then Reggio re-edited the film to fit the music better, then Glass rewrote the music to fit the film better ... I'm not sure how long this went on, but the film as it is was the result.

I have seen Powaqatsi and I was not as impressed with it as the first: the film, in this case, seems tonally at odds with the imagery. I don't know enough about music to explain why, but I can say that the film shows societal change in industrializing nations and the music sounds rejoiceful when the visuals (to me at least) don't seem to justify it.

the film, in this case

The music, rather....

Judging from the amount of time it seems to take Reggio to get a cut, that editing process may have taken a while. I don't know if he suffers from budget constraints or not...I'm under the impression that he'd rather wait to capture the images he wants, rather than settle for something "close." But the film suddenly makes a little more sense, now that you've unveiled it a bit.

poyaanisqatsi was a let-down to most critics as well, after the visual stunnery of the first. i have not seen it, and probably won't ever. but i'm glad i accidentally walked in on this, even if i did have to put up with the pen clicking.

I don't know enough about music to explain why, but I can say that the film shows societal change in industrializing nations and the music sounds rejoiceful when the visuals (to me at least) don't seem to justify it.

now, see, if you were a film critic, you'd have an opinion all wrapped up around this so as to seem an expert on the matter ; )

I wouldn't have been sure of the film's message either if it hadn't been for the definition (life out of balance) and those ending shots of the cave dwellings. it had this incredible archetypal quality to it, just the sort that someone bent on making a film that could be filed under propaganda (but is trying his best to steer away from the label) might use to his advantage.

i liked it, i guess-meaning that i didn't feel tricked or cheated somehow by the ending-because the film held me in suspense but not too much suspense; i.e., i was able to really wrap my brain around these images and connect with them on this level that made the realization that this is my society; ain't it so bizarre? i found it rather thrilling...even more so, after i realized that this was essentially an environmental film (both physically and spiritually)

... i think that the music is meant to denote man's hubris in his own creation, and his blindness to his own destruction; and, possibly, to convey that what man builds is so incongruous with Nature that why we would choose to live the way we do defies all logic

...or, at least, goes against our better instincts. Yet we live like this anyway...

And to touch on the propaganda thing, I don't think it is propaganda. It's cautionary, a warning. But I'm sure some people would disagree.

It's not unlike the monolith that the gorillas gather around at the beginning of 2001.

Powaqatsi translates as "life in transition," and given its settings and Godfrey Reggio's comments about technology becoming a way of life, I think it's safe to say that it's meant to capture the stress that industrialization puts on society, especially in terms of human costs. Visually, it's a beautiful film, like Koyaanisqatsi.

I forgot to mention: Koyaanisqatsi starts off with the cave painting, then the doomed spaceship, then goes into a section on natural beauty which is stunning in its own way: for instance pairing billowing clouds with crashing waves, so that you can see that they must sometimes and somehow be governed by the same principles. Then it returns to evidence of human civilization, with the music shifting markedly in tone and tempo as it does. The cityscapes come in about 30 minutes into the film.

It's such a grim and relentless portrait--but not, I think, an inaccurate one--that by the end I always feel that my throat's tight. That smoking man you have above, in profile in the green lighting, breaks my heart a little bit every time he puts his hand to his forehead. It's a mighty film, really.

Incidentally, one of my professors--a documentary film professor--wouldn't class this as documentary, but propaganda. Why? I wanted to know. How is it that Triumph of the Will, which documents an event through choice of shots and their assembly into a chronology telling a story and putting forth a discernible point of view which most people would agree is repugnant and plainly wrong, gets a free pass but this film doesn't? I never got a satisfactory answer to that.

Wow, was I tired when I wrote Poyaanisqatsi!

(film gods, be kind...)

Glad you set me straight. I thought that I had read that critics had found it disappointing in the 1998 Video Movie Guide, but according to my 2007 copy, Powaqqatsi is "a sumptuous treat for the eyes and ears...gorgeous cinematography...Like it's predecessor, it's an engaging but sober look at what some would call progress." I'll keep that in mind.

As for propaganda...first of all, that's a big word that people like to throw around and through vernacularization, it's become interpretable. But as to why someone might take exception with a film that's very creation foots the classic definition of propaganda, it probably has a lot to do with the filmmaker.

Leni Riefenstahl was only making movies for Hitler to keep herself alive. She was Jewish, but just happened to be the most talented filmmaker in all of Germany, so Hitler employed her rather than waste that talent. What I get from her film Olympia is a distracted sense of her own country and its ruler. Her portrayal of her Kaiser is retrospectively unflattering, although as a rising power in Europe, I imagine when he saw her cut he felt that it accurately reflected his implicit right to his position.

I found that slight discrepancy interesting, like she was using the medium to belittle him visually, while making it seem like she was simply recording a beloved leader. He's quite enthralled with the sports arena. There's one point during a 400m relay race where the German team -- far in the lead -- drops the baton and it's very subtle, but Riefenstahl cuts away to Hitler and his reaction. It's out of place, in a way, indicating this moment where you see a man that she does not like...

In Triumph of the Will, I didn't necessarily get the same sense, but it's been a decade since I watched it. The more important factor, though, may not be any subtle filmmaking ploys in that film, but rather a response on your professor's part to the backlash Leni Riefenstahl got for supporting Hitler, especially before her autobiography came out.

I do think that Powaqqatsi is not as powerful as Koyaanisqatsi--the cinematography is beautiful and the music is wonderful, but for me at least the two don't work well together, diminishing the film's effect. I liked it but didn't love it, and I haven't yet seen the third one, which is about war as a way of life and has generally been reviewed as a disappointment in comparison to its predecessors.

You could be right about my professor's train of thought. It's an ungenerous assessment on my part, but I always was unconvinced by Riefenstahl's denials. I had a cynical suspicion that she stayed because she was enamored with the power and freedom she had as Hitler's favorite filmmaker and/or chose not to know what was going on. But I haven't read her autobiography, and I'm unfairly comparing her to Dietrich, who was also a woman with fame and relative wealth but chose to leave the country.

Have you seen The Wonderful Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl? That's a fascinating film.

No, I haven't seen that movie or read her autobiography (Leni Riefenstahl: A Memoir (1993)) but I did see Downfall, with Bruno Ganz. The film covers the final days of Hitler, beginning with him interviewing several young German women to be his secretary. The film's an accurate account of perhaps the last six months of his life; but, more importantly, it contains footage of the real-life secretary as an old woman, telling her interviewer that she had heard of the atrocities going on but that it just wasn't real to her, or that she just didn't believe them.

Did Marlene Dietrich, a star whose career was made or broken on public opinion, leave Germany because she absolutely knew what was going on and sickened by it, or did she just not want to be associated with bad press and rumors? Riefenstahl claimed political ignorance in her Memoir, and a lot of people didn't believe her...but somewhere between the secretary's admission of her own sort of youthful ignorance and other things I've read about the superstitious nature of a lot of people in Germany, I'm willing to give the Germans some slack.

After reading The Painted Bird, a work of fiction that's set in backwoods Germany just prior to the Kaiser's rise, it's very easy to see how an entire nation could have been completely blind to what was going on and could have very easily dismissed such rumors.

Post a Comment

<< Home