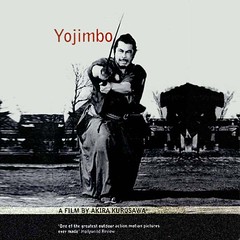

Yojimbo (1961)

Dir. Akira Kurosawa

Writ. Ryuzo Kikushima, Akira Kurosawa

w/ Tohiro Mifune, Tatsuya Nakadai

Writ. Ryuzo Kikushima, Akira Kurosawa

w/ Tohiro Mifune, Tatsuya Nakadai

A samurai was many things in his lifetime: a protector of the realm, a defender of the ruling party, and the iconoclast to whom all other classes gave honor. In Yojimbo, he's also the scruffy wanderer who seeks to find a new place in which to sharpen his skills before they rust, and to do so with as much tact as possible. When Sanjuro walks into a town which has been taken over by a sake dealer named Seibei and a silk dealer named Ushi-Tora, he finds just such the whetting stone for his talents. The merchants, appraising the recent fall of Japan's last dynasty as a time for greed and corruption, have been busy raising their stations by collecting gamblers as cutthroat bodyguards and attacking the farmers who once supplied their trade. Although the samurai has been bereft of food and away from the ruling family he once protected with his life for an unsubstantiated amount of time, he takes his time, sizing up the atmosphere and events carefully. It is a new Japan. One of the merchants has kidnapped a local farmer's attractive wife to negotiate for his son; but, it is a time of social disorder and chaos. It is a time when some parents advise their son to kill to win the respect of men while yet others advise staying on the farm and reaping an honest day's work.

Eh, parental expectations can be heavy, you know?

Eh, parental expectations can be heavy, you know?

Samurai as Loner: a Study in Contradiction

Humility comingles with self-sufficience in the lonely, wayward manifestation of Tohiro Mifune's chest-scratching, abrasive Sanjuro. His very name, pulled from the mulberry fields that are the conspicuous focus of his enigmatic stare, elicits a sense of dissipatory elusiveness that supercedes all of his actions. When he lets the stick fall where it will and follows, he acknowledges that his destiny lies outside of his hands. Like the restless, roving, and ultimately crumbling samurai class to which he belongs, though, this unforgettable visual component acts as deft commentary on the unforeseeable -- but just as precarious -- future of Japan.

Keiko I. McDonald's extensive look at the historically-based but aesthetically licensed milieu Kurosawa creates in Yojimbo explains the four-tiered class system as having the samurai at the top, followed by the farmer, with the artisan and the merchant comprising the bottom, respectively. [1] Having been abandoned by the Tokugawa Shogunate's corruption and collapse, the classes have been left in the rapacious lurch of the feudal system, Sanjuro included. "Kurosawa's camera, focusing on the protagonist's back for an unusually long time, evokes a sense of claustrophobia," writes McDonald. "At the same time the white family crest in the center of Sanjuro's black kimono becomes fixed in our minds." Even freed from his masters, this suggests that the samurai was still burdened with the honor expected from one of his ilk though it fails to benefit him in any tangible way. Alone, hungry, and unemployed, he moves on.

The town he arrives in has been overrun by merchant-class opportunists -- a sake dealer and a silk dealer who have each conspired with gamblers in an effort to amass muscle power and outdo the other. Ever aloof to those he claims to despise as weak and defenseless, Sanjuro appears to play heartless games of mischief as he sets the merchants and their men against each other. The open conflict this generates between the two factions acts as representative of the hard realities of that time. Despite his outward enjoyment of the goings-on, though, his alternate side emerges to reveal the inner hero. Tough love is deeply ingrained in his bluff sense of altruism, and deep down he's a role model as well as the protector of an abandoned people he loves.

Samurai as Mediator: the Strategist vs. the Humanitarian

Perhaps the most curious aspect of Yojimbo, Kurosawa's carefully constructed removal of Sanjuro from the story's more criminal elements, deters the audience from seeing the samurai too closely, nor too disjointedly. Effectually, the audience sees much through his eyes while still being allowed the advantage of telling camera work that plays all over Mifune's physique. In a studied scene in which he learns all about the town and its oily operations, Sanjuro and the old man who feeds him pace around the interior of a hut in the foreground while the middle ground remains largely empty of action and seemingly devoid of life. In the back ground, in deep focus and employing a playful Japanese sense of mise-en-scène, the merchants' men grease the official inspector's palms with money and flood his tea cup with sake. "In this town, I'll get paid for killing," Sanjuro ruminates as he watches these subtle announcements of the deterioration of his culture, "and this town is full of men who are better off dead."

Yet, Sanjuro still finds humor in the buying-off of the officials; it's the deeper aspects of cultural erosion that trouble him. The silk merchant's prayer chanting for the death of the sake merchant denotes the perversion of religion. McDonald's observation succinctly grasps the tension of these scenes: "As the coffin maker's hammer and the silk merchant's prayer drum beat together on the sound track, we realize that religion, traditionally the answer to death, is no longer an answer or a solace; that, ironically, death is the 'answer' to 'religion.'" The palpitations of the steady march of time in an era of decline reverberate throughout Yojimbo's stark landscape, signalling a sort of death pall that Roger Ebert summed up well when he wrote, "Shutters, sliding doors and foreground objects bring events into view and then obscure them, and we get a sense of the town as a collection of fearful eyes granted an uncertain view of certain danger." [2] As the audience, perhaps, we are immune to that fear; it has, though, at very least become a tangible and calculable presence among the marginalized and deserted townsfolk.

Further exacerbating the face of death in isolation is the dual irony presented by Sanjuro auctioning off his services as bodyguard to the highest bidder. For one thing, all things monetary are beneath a samurai's dignity; that he must pretend to an ignominy that he doesn't come by honestly holds irony enough. His choice of masters, though, betrays his true ingenuity. Seemingly, by offering these services at all, he validates the self-importance that these bosses draw to themselves while what he's really doing is using it against them to complete the ruse. It is the people who must be protected from the war-mongering merchants who have superceded their place in society and shunned the farmers and artisans whom they once depended upon. It is the emerging middle class that Sanjuro elects to pick out, then, by using their own vanity and opportunism against them however he can in order to save the true people of Japan.

Samurai as Paragon: the Transitional Navigator

No mere sorter of souls, though, Sanjuro's egalitarian view shines through, especially with regard to the decisions all men must make. He never pretends to be more than what he is: unemployed. His fellow samurai, although in a seeming position of disgrace and laziness, prompts his respect as a fellow loner and entrepeneur. The swift reduction of the merchants' houses essentially reduces its leaders to opposing vices. Humor remains the ultimate mediator between murderous intent and natural justice. By not backing down from a pistol clearly aimed at him, Sanjuro cedes the right of way to destiny, even if it means death, and even if it's his own. This singular aspect of the samurai's prescience of mind and honor in times of crisis touts the grand ideal that that sort of warrior has inspired generations since. His tacit gravitation to where he's needed most could be argued as the happenstance of a life spent defending royalty and personifying nobility. That would be a good argument. It would be better, though, were we to see that the farmers and artisans left behind by the collapse of the last Japanese Dynasty made the people, in this time of sorrow and change, his new and implicitly truest royalty.

[1] McDonald, Keiko I. Swordsmanship and Gamesmanship: Historical Kurosawa's Milieu in Yojimbo. Literature Film Quarterly, 1980, Vol. 8 Issue 3, p188, 9p; (AN 6906904)

McDonald interviewed both the famed Kurosawa writer Donald Richie and Yojimbo cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa and drew heavily on Richie's Japanese Cinema: Film Style and National Character and The Films of Akira Kurosawa.

[2] The incomparable Roger Ebert.

3 Comments:

I had Keiko McDonald for a class at Pitt nearly 20 years ago called "Westerns and Samurai." It was one of the best courses of my college career and it founded my appreciation for Japanese cinema and broadened my appreciation of the American Western.

Thanks for the posting so that I could renew, honor and respect that experience.

You're very welcome.

If you have access to the Ebsco database, you can find his extremely well-written article under "Film and Television," I believe.

I've broadened my appreciation of the American Western since starting this blog and researching, too. Wasn't much of a fan in my girlhood.

I appreciate how Kurosawa portrays the complexities and contradictions within a lone Samurai navigating societal upheaval.

Post a Comment

<< Home